The 2021 general election in Peru was one of the most contentious in recent memory.

In the first round, on April 11, voters expressed disapproval of the political class as whole.

With the highest COVID-19 mortality rate in the world, and an 11 percent economic contraction in 2020, it was perhaps unsurprising that no candidate exceeded the number of blank and spoiled ballots.

Que se vayan todos was the resounding message—out with them all!

The most successful candidate was Pedro Castillo, who won 19 percent of the valid votes cast, followed by Keiko Fujimori with 13 percent.

The remaining votes were distributed among 16 unsuccessful candidates, including, on the right Rafael López Aliaga and Hernando de Soto, on the left Verónica Mendoza, and in the center Yonhy Lescano.

A runoff between front-runners Castillo and Fujimori was scheduled for June 6, 2021.

For the two-thirds of the electorate who did not vote for these candidates in the first round, the choice was stark and difficult.

The presidential and congressional election results showed that the median Peruvian voter leaned right, making Castillo unpalatable.

Yet Fujimori was unacceptable to many voters, both because of her association with the authoritarian regime of her imprisoned father, Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000), and due to her own history of undermining and obstructing previous democratic governments.

Pedro Castillo won the runoff by an exceptionally narrow margin—50.1 percent—and was declared President only after the National Election Board dismissed a flurry of challenges from Fujimori’s legal team involving baseless allegations of fraud and other irregularities.

The geography of the vote revealed a country deeply divided along regional lines, with Castillo winning overwhelming support in the highlands, especially the south, and Fujimori carrying Lima and the coast, especially the north.

One reason for Castillo’s success appears to have been his position on mining.

Castillo performed well in the corredor minero del sur, or southern mining corridor, which includes three major regions: Cusco, Arequipa, and Apurimac.

This was a crucial battleground for both candidates.

Having lost in these regions during her last two attempts at the presidency, Fujimori made a radical proposal in 2021: to directly redistribute mining revenues to voters.

Pedro Castillo proposed a change in the distribution of mining revenue at the state level, where only 30 percent of would be pocketed by the company and 70 would be used by the Peruvian government to fund development programs.

Despite Fujimori’s populist appeal, voters in mining areas overwhelmingly favoured Castillo at the polls.

Given Castillo’s narrow margin of victory, Fujimori’s inability to sway voters in the mining corridor likely cost her the election.

Why did Fujimori’s proposal fail to win over the mining vote?

To answer this, we look at the political economy of mining and the campaign strategies of the candidates.

Mining in Peru

Mining has long been the basis of Peru’s political economy.

Even after the commodity boom of 2009-2013 came to an end, mining remained one of the most important economic activities in the country both in terms of tax revenue and exports, and has consistently been the leading sector in foreign direct investment, accounting for 23 percent of it. In 2020, mining investment contributed $4.3 billion USD, exceeding their annual goal by 3 percent despite the COVID-19 pandemic (MINEM, 2021).

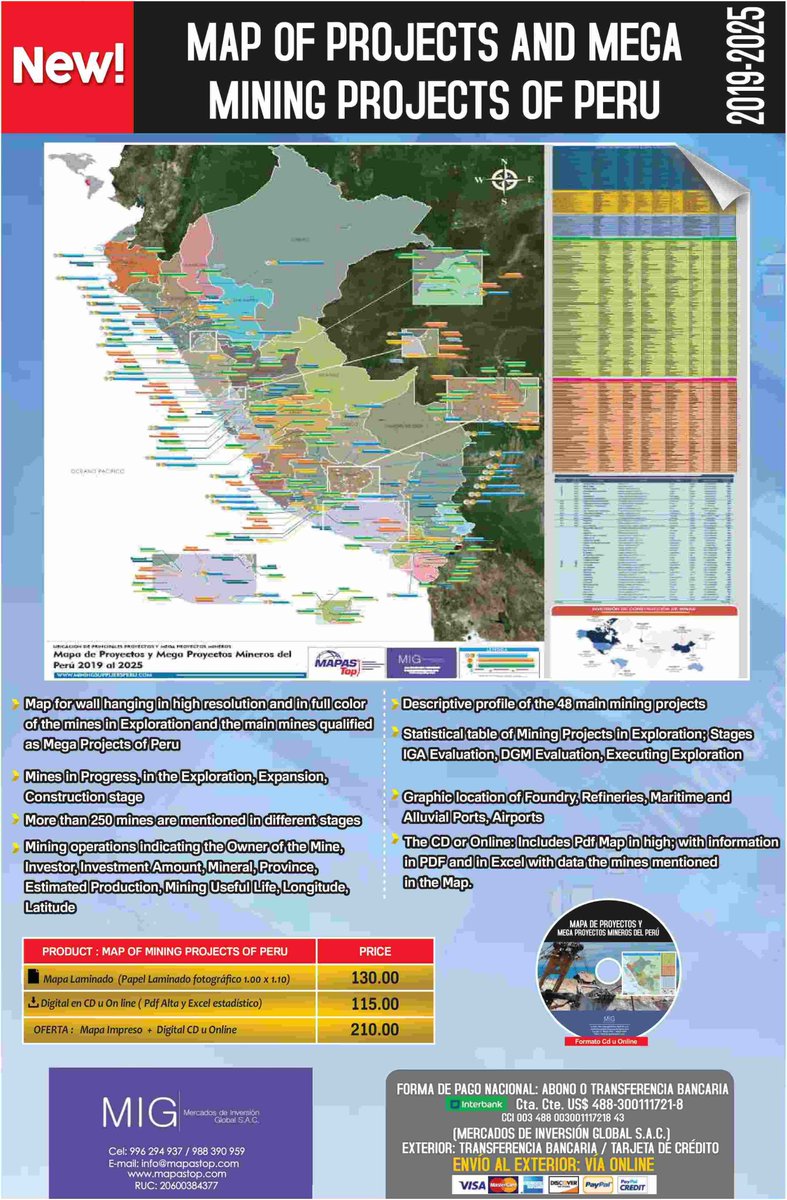

Additional mining projects have been inaugurated in recent years, and revenue from mining is expected to continue growing despite the pandemic.

While the economic and political establishment promotes mining investment with a new discourse of environmentally and socially responsible mining (Himley, 2014), citizens living in close proximity to mining sites have continued to challenge the expansion of the industry.

The Ombudsman Office recorded 1,460 conflicts around mining in the period 2008-2019, with over 37 percent of them classified as episodes of violence (Defensoria del Pueblo, 2019).

The pandemic did not disrupt this trend of mining expansion and conflict.

Initially, as part of the government’s COVID-19 response, mining projects were ordered to stop all activity.

However, large-scale mining was quickly exempted from quarantine measures (Vila Benites & Bebbington, 2020), and the Ministry of Energy and Mining announced that the new mining portfolio includes over 60 projects that amount to over 500 million USD in investment (MINEM, 2021b).

After mining activities were restored, the rate of social conflict returned to usual levels.

In 2019, the Ombudsman Office recorded 59 active conflicts associated with mining activities a month, with a majority concentrated in the Andean highlands of the country.

In July 2021, the same office recorded 60 active mining conflicts (Defensoria del Pueblo, 2021).

Mining conflicts are rooted in demands for economic redistribution of benefits and environmental concerns.

Citizens living in areas of oil and mining projects are exposed to the externalities of extraction such as increases in local poverty levels (Cust & Poelhekke, 2015), environmental degradation (Eisenstadt & West, 2017) and social fragmentation (Svampa, 2019).

Citizens mobilize around these issues through coordinated networks of cooperation with local community members, but protest usually remains localized because the communities are isolated from neighboring localities with similar problems (Paredes, 2016).

As part of a new approach to mining, the Peruvian state has implemented measures for social and environmental regulation such as the prior, free and informed consent processes for Indigenous peoples and community participation in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process.

Due to the asymmetric relationship between state corporations and the communities, and the limits of enforceability of agreements (Flemmer & Schilling-Vacaflor, 2015), however, these participatory spaces have had little impact on the rate of social mobilization around mining extraction in the country.

Moreover, although the discourse of the new mining policies promotes the peaceful resolution of conflicts, in some cases the state has been quick to respond with the use of violent repression to guarantee the continuation of mining operations (Taylor & Bonner, 2017).

The limited capacity of governments, from both left and right, to address the demands of citizens living in mining areas (Riofrancos, 2021) has hurt the legitimacy of the state and the political class.

References

Cust, J. and Poelhekke, S. (2015) ‘The Local Economic Impacts of Natural Resource Extraction’, Annual Review of Resource Economics, 7(1), pp. 251–268.

Defensoria del Pueblo (2019) Base de Datos de Conflictos Sociales. Respuesta a solicitud de acceso a la información publica.

Defensoria del Pueblo (2021) Reporte de Conflictos Sociales N 209. Access: https://www.defensoria.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Reporte-Mensual-de-Conflictos-Sociales-N°-209-julio-2021.pdf

Eisenstadt, T. A. and West, K. J. (2017) ‘Public opinion, vulnerability, and living with extraction on Ecuador’s Oil Frontier: Where the debate between development and environmentalism gets personal’, Comparative Politics, 49(2), pp. 231–251.

Flemmer, R., & Schilling-Vacaflor, A. (2015). Unfulfilled promises of the consultation

approach: the limits of effective indigenous participation in Bolivia’s and Peru’s extractive industries. Third World Quarterly.

Himley, M. (2014). Mining History: Mobilizing The Past In Struggles Over Mineral Extraction In Peru. Geographical Review, 104 (2), 174-191.

MINEM (2021) Anuario Minero 2020: Reporte Estadistico. Lima: Peru.

MINEM (2021b) Cartera de Proyectos de Exploracion Minera 2021, Ministerio de Energia y Minas. Lima: Peru.

Paredes, M. (2016) ‘The glocalization of mining conflict: Cases from Peru’, Extractive Industries and Society. Elsevier Ltd., 3(4), pp. 1046–1057.

Riofrancos, T. (2020). Resource Radicals: From Petro-Nationalism to Post-Extractivism in Ecuador. Durham: Duke University Press.

Taylor, A. and Bonner, M.D. (2017) ‘Policing economic growth: Mining, protest, and state discourse in Peru and Argentina’, Latin American Research Review, 52(1), pp. 3–17.

Vila Benites, G., & Bebbington, A. (2020). Political settlements and the governance of COVID-19: Mining, risk, and territorial control in Peru. Journal of Latin American Geography, 19(3), 215-223.

First published in the LASA Forum, Vol. 52, no. 4, Fall, 2021, pp. 45-50)

Verónica Hurtado is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Her research areas are political economy of development and political behavior for Latin America, focusing on subnational variation and resource-dependent states.

Using a mixed-method approach that combines comparative historical analysis, network analysis, and survey experiments, her dissertation analyzes the origin and evolution of populist mobilization in two Andean countries: Peru and Bolivia.

Her research has been generously supported by the Liu Scholar Fellowship, the UBC Dissertation Award, and the Evidence in Governance and Politics (EGAP) network at the University of California Berkeley.

She holds an M.A. in Political Science from UBC and a B.A. in Political Science from the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Maxwell A. Cameron is Professor in the Department of Political at the University of British Columbia.

He specializes in comparative politics, democracy and ethics.

His publications include Democracy and Authoritarianism in Peru (St. Martin’s 1994), The Peruvian Labyrinth (Penn State University Press, 1997), Latin America’s Left Turns (Lynne Rienner, 2010), Democracia en la Region Andina (Lima: IEP, 2010), New Institutions for Participatory Democracy in Latin America (Palgrave 2012), The Making of NAFTA (Cornell, 2000), Strong Constitutions (Oxford University Press 2013), Political Institutions and Practical Wisdom (Oxford University Press, 2018) and over 50 peer reviewed articles.

Cameron has taught at Carleton University, Yale University and the Colegio de Mexico.

Between 2011-2019 he served as the Director of the Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions.

In 2013 Cameron won a UBC Killam Teaching Prize and in 2020 he became the Canadian Association of Latin American and Caribbean Studies’ Distinguished Fellow.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of CEIM. Any content provided by our bloggers or authors are of their opinion. The content on this site does not constitute endorsement of any political affiliation and does not reflect opinions from members of the staff and board.