The competition for mining votes

Presidential candidates have appealed to voters in mining areas proposing new schemes of revenue redistribution as well as more strict requirements for environmental and social protection.

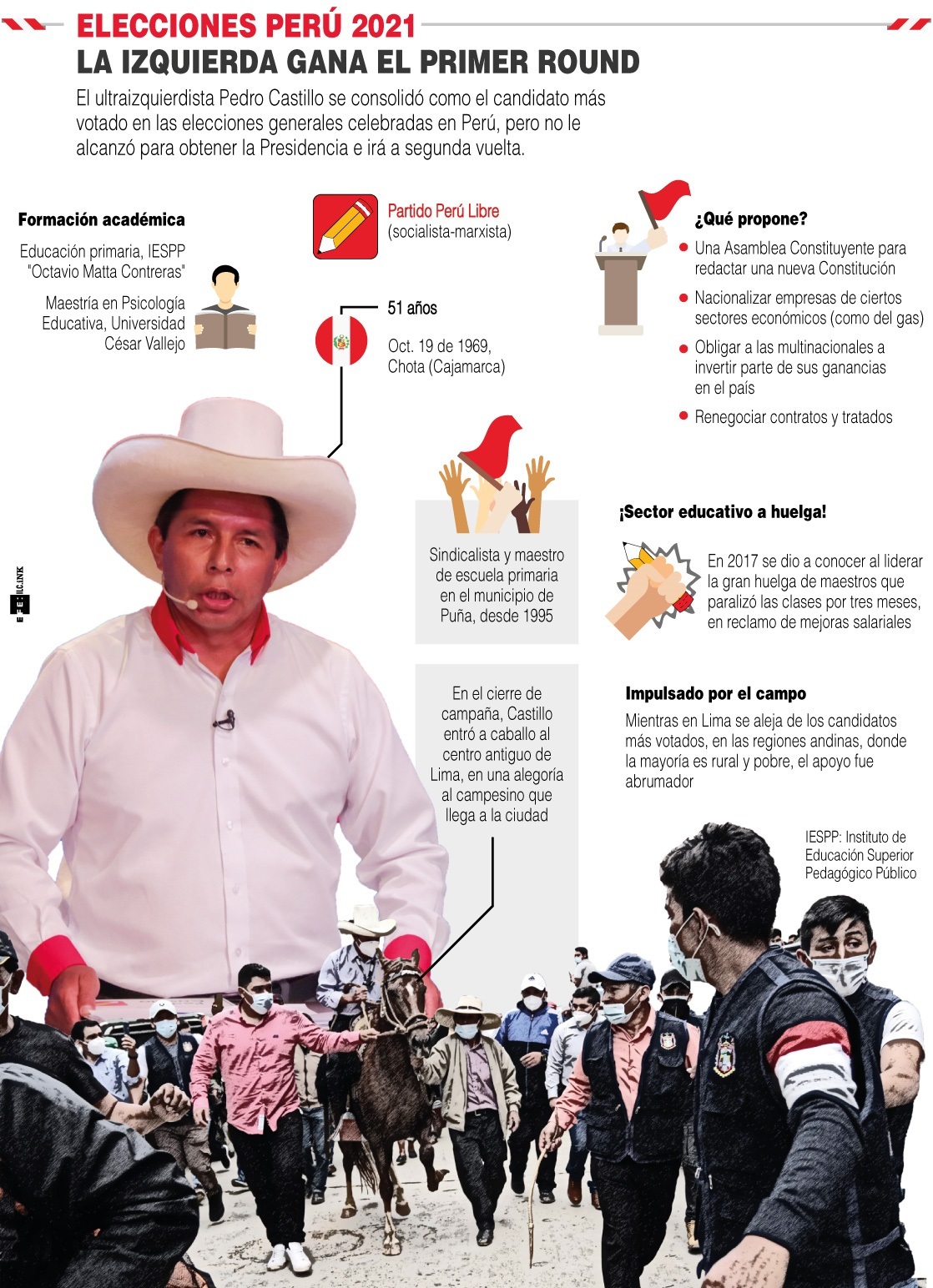

A month before the first-round vote, Castillo barely registered in the polls.

The then front runner, Yonhy Lescano, a law professor and former member of congress who represented Puno in the southern highlands for the centre-right Acción Popular party, advocated for a greater share of mining revenue to go to the state.

He proposed a 50-50 profit sharing arrangement, suggesting that the idea of demanding more from mining companies had already become part of mainstream political discourse (Wyss 2021).

Veronika Mendoza, a former congresswoman from Cusco and presidential candidate from a left-wing party, campaign with a discourse focused on reducing economic dependency on mining and strengthening the institutions in charge of environmental regulation.

Castillo outperformed Lescano in the mining regions.

During the campaign, he was sharply critical of large mining companies and the failure of the national state to contribute to the development of mining communities.

He claimed that the state, supported by higher taxes, could assume a more central role in the development of rural regions.

Bolivia was held up as evidence that this change would not necessarily lead to a loss of investment.

His proposals highlighted the role of binding consultation processes, whereby communities would be given the ability to veto the development of mining investment in their territory.

In areas where social conflict has halted mining expansion, Castillo was also the favourite with over 40 percent of the votes in the first round, and social leaders recognized that Castillo’s proposals around mining were key in mobilizing voters in these regions (see interviews in Muqui, 2021).

Polls published immediately after the first round showed Castillo with an ample lead over Fujimori (Ipsos, 2021).

Voters were receptive to Castillo’s call for “no more poor people in a rich country.”

Finding herself in competition with a radical leftwing candidate promising significant redistributive reforms, Fujimori was compelled to pivot with her own message.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/OKAW7PIYMRAKVKSIML5AYXFUSQ.jpeg)

She argued that the main obstacle to development was subnational corruption, and pointed her finger at subnational authorities who misused the mining canon (a term used to refer to the system for distributing mining royalties to subnational authorities).

As an alternative, she proposed to create a program for the direct transfers of benefits to the families living in close geographical proximity to mining projects.

Fujimori’s strategy of blaming governors and local authorities for bad management of canon resources may have misfired.

First, by blaming lack of development on corruption at the sub-national level, she let the mining industry itself off the hook.

Yet many companies are the focus of anger and resentment among local communities due to environmental destruction and wealth accumulation in the midst of desperate poverty.

In the LAPOP 2018 survey, 20% of Peruvian respondents indicated that extractive industries, including mining companies are the main source of environmental pollution in the country.

Her proposal of revenue redistribution was isolated from her larger agenda of promoting mining investment, even for projects that had been halted due to social conflict.

Second, although corruption is notorious among local mayors and governors, it is not clear that citizens’ blame them for underdevelopment in mining areas.

Subnational authorities do, however, manage resources upon which some segments of the population depend and are usually considered allies when mining conflict erupts.

Third, Fujimori’s strategy was focused on the communities’ economic grievances, but did not propose to increase the takings of the state from the companies and discounted the environmental concerns that mobilize voters in these areas.

The direct redistribution of mining revenues would increase voters’ purchasing power, but would not change the relationship between state, mining companies, and communities.

If anything, the proposal would further weaken the role of the state in areas where its capacity was already limited.

In contrast, Castillo’s proposals targeted social dynamics of organization in mining regions by focusing on the corporations and the state, as well as highlighting the role of communities in local investment decisions.

These ambitious proposals attracted voters not only because Castillo fit the profile of the typical outsider politician, but also because his candidacy had the support of social organizations such as the rondas campesinas (peasant self-defense organizations) and the teacher unions.

Given his past as a grassroots leader, voters might have been more willing to trust his proposals to reshape the model of extractivism that has excluded or neglected mining communities. In mining regions, candidates with similar profiles, such as Ollanta Humala in 2011 and Veronika Mendoza in 2016, have been favoured during presidential elections, and others have reached subnational office, such as Oscar Mollohuanca in Espinar, Cusco, and Walter Aduviri in Puno.

Rural voters identified Fujimori with the establishment, despite her best efforts to distance herself from it—and indeed, implausibly, to claim that Castillo represented both communism and continuity with the past.

Consequently, the proposal for direct cash transfers was either discounted as lacking credibility, or was not seen as addressing the main grievances of the population—for example, the need for better environment protection and sustainable growth in peasant communities. Castillo, by contrast, presented himself as an outsider challenging the establishment on behalf of the marginalized communities of the highlands, of which he was a member. He was perceived by these communities as more trustworthy, less corrupt, and perhaps more accountable to his electoral base.

What should we expect from Castillo?

In a word, uncertainty. While Castillo secured over 65 percent of the vote in mining regions during the second-round, the government has yet to execute the new taxation scheme to large mining.

So far, there is no clear plan for implementing the commitments he made to Indigenous people and environmentalist groups during the campaign.

His newly appointed Minister of Energy and Mines, Ivan Merino, a member of Peru Libre, has introduced the concept of “social profitability” but it is unclear what this means for the mining industry.

In his inaugural presidential address, Castillo referred to the importance of the role of the state in securing socially responsible mining, and ensuring communities are in charge of their own destiny.

Guido Bellido, the president of the cabinet, has indicated that, although he will respect private investment, he wants greater state involvement in energy projects, including gas and hydro.

This potentially has implications for the Camisea gas project, led by a consortium of foreign companies. Bellido was dispatched to deal with a mining conflict in the Las Bambas mine, a copper project operated by the Chinese firm MMG.

The protesters were mollified by Bellido’s intervention and criticisms of the company but the conflict remains unresolved.

The mining industry is concerned with the possibility of new taxes. Roque Benavides, the President of the Buenaventura Mining Company, and one of the leaders in the mining sector, has been open to dialogue with Castillo.

Benavides has stated that political stability during Castillo’s presidency is important for the economic future of the country.

Since mining companies tend to have long time horizons, and with copper prices at an all-time high, it may be possible for Castillo to negotiate an arrangement with this fraction of Peru’s business class on the understanding that, in return for cashing in on another bonanza, the state takes a larger share of the revenue.

Conclusion

Is Peru about to embark upon a radical change in the role of mining in the prevailing economic model? Is there enough popular support for such a change? On this point, we are cautious.

The government is highly precarious, lacking in support from Congress, and it faces enormous political resistance from powerful economic groups and the media. Moreover, the public is divided.

The election could have had a very different outcome. Had Lescano held his lead for a few more weeks, for example, the second round could well have produced a mandate for a centrist government willing to renegotiate terms of investment with mining and gas companies but without challenging the economic model.

At the same time, the election revealed that Peru remains deeply divided along rural-urban and north-south lines.

The current neoliberal economic model has failed to generate sustainable and shared prosperity.

The degree to which it has also left most Peruvians vulnerable has been dramatically underscored by the pandemic and its economic consequences.

It is unsurprising that the mining industry, which has emerged largely intact, has become the focus of attention as Peruvians struggle with how to pay for needed and long-postponed reforms in healthcare, education, and local development.

Whether the Castillo government can survive long enough to pose a credible alternative to the current development model is unclear. Even less clear is how, as an instance of the left in power, it will manage the inevitable tensions between resource development and post-extractivism (Riofrancos 2020).

The idea of buen vivir, or living well, evoked by Pedro Francke when he was sworn in as Economy Minister, has come to symbolize a desire for a new relationship with the earth which can conflict with the need to reduce poverty through industrialization.

This tension was present in the decisions of the Bolivian government of Evo Morales as it grappled with road construction through the TIPNIS national park, and in struggle over oil extraction in the Yasuni National Park during the government of Rafael Correa in Ecuador.

Indeed, the left presented two options in the recent election in Ecuador, one of which was of a developmentalist orientation, the other and advocate of Indigenous rights.

The primary focus of the Castillo government during the first months of government will be addressing the pandemic and surviving in the short term in the face of strident and an increasingly authoritarian, indeed Trumpian, right-wing opposition.

If it manages to survive, there is no question that, at a minimum, rents from mining will be necessary to pay for its ambitious social policies.

References

Ipsos (2020) Opinion Data – Abril 2021. Access: https://www.ipsos.com/es-pe/opinion-data-abril-2021

Muqui (2021) ¿Por qué Pedro Castillo ganó en provincias donde rechazan los proyectos Río Blanco, Conga y Tía María?. Red Muqui. Access: https://muqui.org/noticias/por-que-pedro-castillo-gano-en-provincias-donde-rechazan-los-proyectos-rio-blanco-conga-y-tia-maria/

Riofrancos, T. (2020). Resource Radicals: From Petro-Nationalism to Post-Extractivism in Ecuador. Durham: Duke University Press.

Wyss, J. (2021). “Companies Keep Too Much of Peru’s Metal Weath, Top Candidate Says,” Bloomberg, March 24. Available: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-03-24/companies-keep-too-much-of-peru-metal-wealth-top-candidate-says [Last accessed: August 11, 2021].

First published in the LASA Forum, Vol. 52, no. 4, Fall, 2021, pp. 45-50)

Verónica Hurtado is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Her research areas are political economy of development and political behavior for Latin America, focusing on subnational variation and resource-dependent states.

Using a mixed-method approach that combines comparative historical analysis, network analysis, and survey experiments, her dissertation analyzes the origin and evolution of populist mobilization in two Andean countries: Peru and Bolivia.

Her research has been generously supported by the Liu Scholar Fellowship, the UBC Dissertation Award, and the Evidence in Governance and Politics (EGAP) network at the University of California Berkeley.

She holds an M.A. in Political Science from UBC and a B.A. in Political Science from the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Maxwell A. Cameron is Professor in the Department of Political at the University of British Columbia.

He specializes in comparative politics, democracy and ethics.

His publications include Democracy and Authoritarianism in Peru (St. Martin’s 1994), The Peruvian Labyrinth (Penn State University Press, 1997), Latin America’s Left Turns (Lynne Rienner, 2010), Democracia en la Region Andina (Lima: IEP, 2010), New Institutions for Participatory Democracy in Latin America (Palgrave 2012), The Making of NAFTA (Cornell, 2000), Strong Constitutions (Oxford University Press 2013), Political Institutions and Practical Wisdom (Oxford University Press, 2018) and over 50 peer reviewed articles.

Cameron has taught at Carleton University, Yale University and the Colegio de Mexico.

Between 2011-2019 he served as the Director of the Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions.

In 2013 Cameron won a UBC Killam Teaching Prize and in 2020 he became the Canadian Association of Latin American and Caribbean Studies’ Distinguished Fellow.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of CEIM. Any content provided by our bloggers or authors are of their opinion. The content on this site does not constitute endorsement of any political affiliation and does not reflect opinions from members of the staff and board.